Horatio Walpole (1717-1797), 4th Earl of Orford, also known as Horace Walpole, was a writer, historian, politician and tastemaker. Of his many pursuits, he is notably remembered for his neo-Gothic home Strawberry Hill, which housed his collection of antiquarian works of art, as well as contemporary ceramics of his day. Unwed and with no issue, Walpole was devoted to amassing his expansive collection. In 1818, William Hazlitt (1778-1830) remarks ‘his mind as well as his house, was piled up with Dresden china, and illuminated through painted glass’.

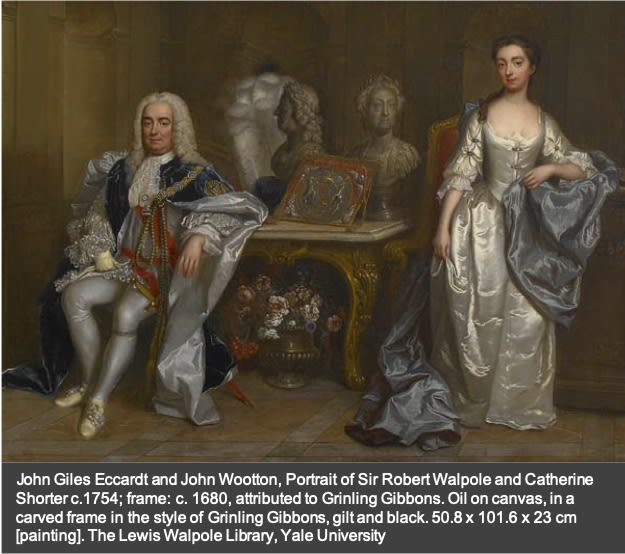

As the youngest son of Sir Robert Walpole (1676-1745), Britain’s first prime minister, and Lady Catherine Walpole (née Shorter; 1682-1737), Walpole inherited his aristocratic taste and collecting practice from both parents. From his mother, Walpole inherited both Chinese porcelain and a taste for the French rococo style, and from his father he received financial security through three lifetime sinecure offices, as well as a taste for Roman classicism.

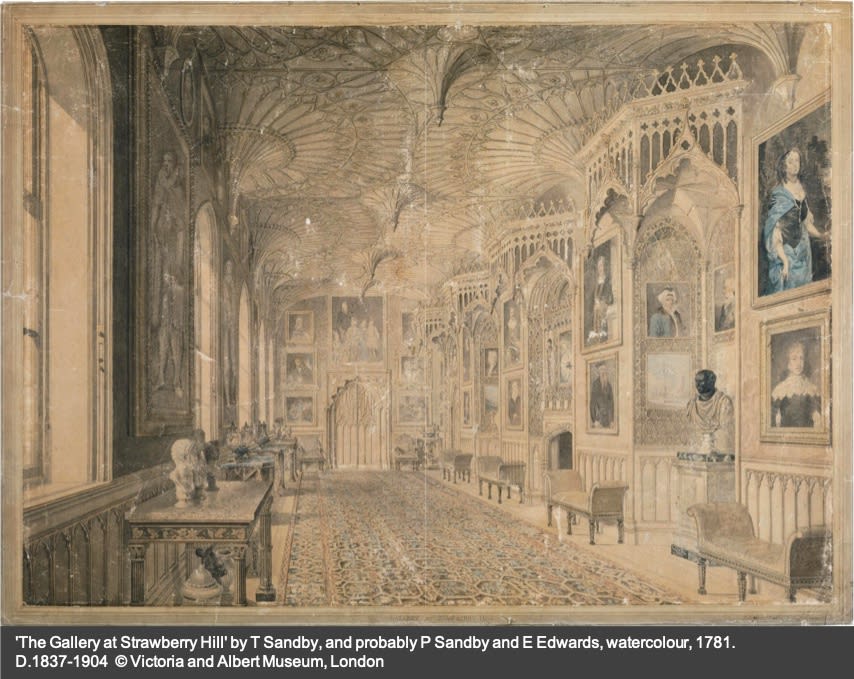

As the youngest child, Walpole was doted upon by his mother, while his father was often away from home engaged with politics at court. As a child, his mother’s French taste influenced his own appreciation for painters such as Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684-1721). However, a visit to the neo-Palladian family seat of Houghton Hall in 1738 introduced the young Walpole to his father’s princely Roman collection of Baroque artefacts. In 1740, Walpole set off on his Grand Tour of France and Italy. In Florence, he would meet his father’s supplier of fine works of art, Sir Horace Mann (1706-1786). Upon his return to Britain, Walpole gained a newfound appreciation for his father’s collection and incorporated rare prints and objets by Italian masters into his own collection at Strawberry Hill, including examples of Italian maiolica. Where most of his ceramic collection was displayed in the China Room, it is worth noting that Walpole displayed his istoriata wares alongside hanging pictures in rooms such as the Gallery or the Round Drawing Room, and among his most treasured objects in the Great North Bedchamber. Displayed flat and sometimes even framed, these maiolica wares, with their finely painted scenes of historical and mythological significance, were clearly prized by Walpole. We can imagine this Fine Urbino Maiolica Istoriato Dish, depicting a scene of the Adoration of the Magi after Giovanni Battista Franco, set against the golden halls of his Gallery.

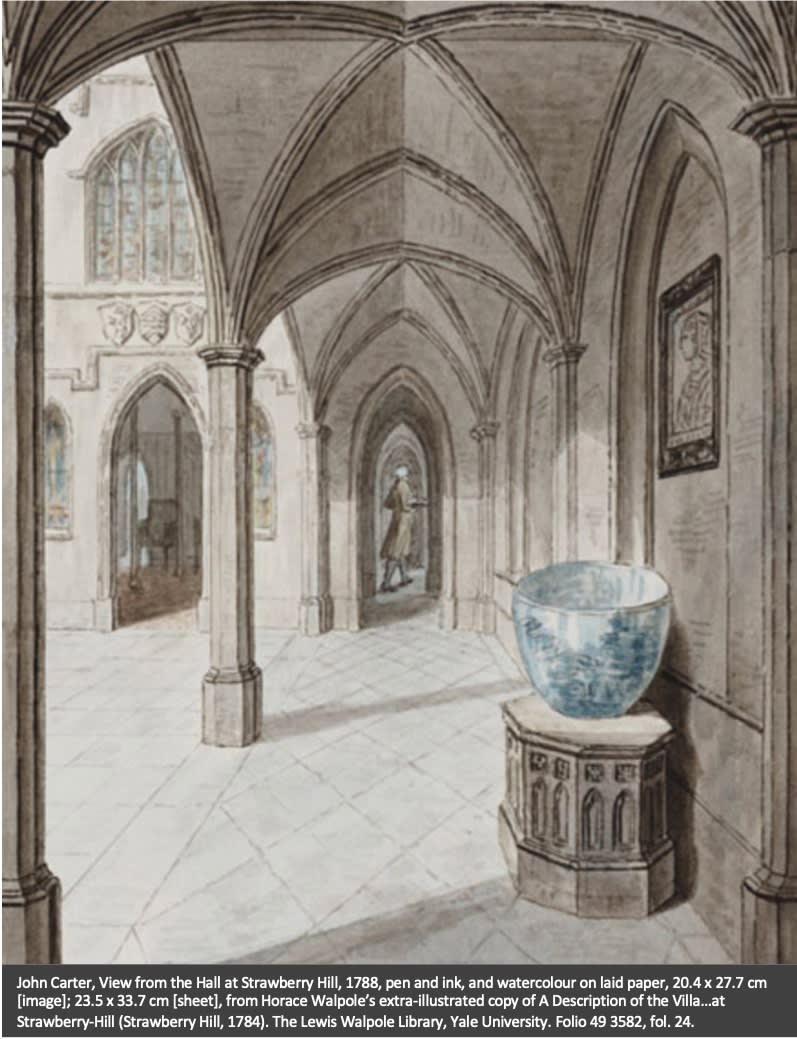

Strawberry Hill was Horace Walpole’s country villa situated on the outskirts of London beside the Thames river in Twickenham. The land was acquired in 1747 and development of the estate began in 1751 by an assembled group of friends, the architect John Chute (1701-1776) and the artist Richard Bentley (1708-1782). Together, they were committed to reproducing a genuine representation of Gothic architecture and formed the ‘Strawberry Committee’ or the ‘Committee of Taste’. Walpole’s adoption of the gothic style enabled his expression of the sublime and the beautiful, where objects set in the high arches and towers of gothic architecture ‘give a whimsical air of novelty that is very pleasing’.

Walpole’s use of atmospheric light and shadow cast objects in various moods. His mother’s blue and white porcelain, embodying exotic appeal and oriental mystery, was displayed on Gothic pedestals next to grand Baroque portraits. Designed to be both intimate and cavernous, Walpole endeavoured to acquire objects for his space which allowed both close admiration and large-scale appeal. Not all visitors and inhabitants, however, met a happy fate at Strawberry Hill.

Walpole’s favourite cat, Selima, met her unlikely doom fishing for goldfish in his large blue and white Kangxi porcelain jardiniere. While we know he did not collect porcelain animal figures, such as the rare examples of Meissen cats modelled by J.J. Kaendler, had he done so, perhaps curiosity would not have killed the cat.

While Selima may not be immortalised in clay, a worthy tribute was made to her by Walpole’s Etonian friend, the poet Thomas Gray (1716-1771).

Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat Drowned in a Tub of Goldfishes

By Thomas Gray

’Twas on a lofty vase’s side,

Where China’s gayest art had dyed

The azure flowers that blow;

Demurest of the tabby kind,

The pensive Selima, reclined,

Gazed on the lake below.

Her conscious tail her joy declared;

The fair round face, the snowy beard,

The velvet of her paws,

Her coat, that with the tortoise vies,

Her ears of jet, and emerald eyes,

She saw; and purred applause.

Still had she gazed; but ’midst the tide

Two angel forms were seen to glide,

The genii of the stream;

Their scaly armour’s Tyrian hue

Through richest purple to the view

Betrayed a golden gleam.

The hapless nymph with wonder saw;

A whisker first and then a claw,

With many an ardent wish,

She stretched in vain to reach the prize.

What female heart can gold despise?

What cat’s averse to fish?

Presumptuous maid! with looks intent

Again she stretch’d, again she bent,

Nor knew the gulf between.

(Malignant Fate sat by, and smiled)

The slippery verge her feet beguiled,

She tumbled headlong in.

Eight times emerging from the flood

She mewed to every watery god,

Some speedy aid to send.

No dolphin came, no Nereid stirred;

Nor cruel Tom, nor Susan heard;

A Favourite has no friend!

From hence, ye beauties, undeceived,

Know, one false step is ne’er retrieved,

And be with caution bold.

Not all that tempts your wandering eyes

And heedless hearts, is lawful prize;

Nor all that glisters, gold.

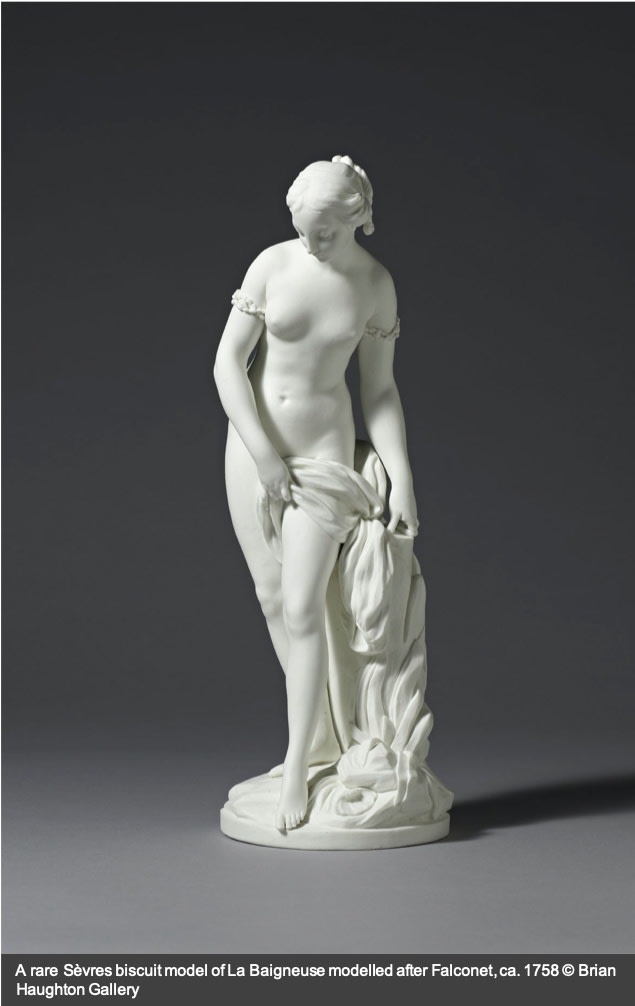

Of the contemporary porcelain available to Walpole, he was particularly drawn to Sèvres and expressed strong opinions on their display. Sculptural figures, such as this Sèvres biscuit model of La Baigneuse, was displayed on mantlepieces, rather than on the dining table, which was the fashion.

In his correspondence to Sir Horace Mann, he writes, ‘Jellies, biscuits, sugar-plumbs, and creams have long given way to harlequins, gondeliers, Turks, Chinese, and Shepherdesses of Saxon China. But these, unconnected, and only seeming to wander among groves of curled paper and silk flowers, were soon discovered to be too insipid and unmeaning…’.

Walpole’s collection contained several Sèvres objects but were primarily examples of teacups and saucers, as well as other domestic wares one would expect to see in the bedchamber to be used and admired privately. As he was unable to purchase and entertain at the scale of his aristocratic peers, examples such as this fine pair of Sèvres Seaux à Liqueur, which formed part of a greater service, would unfortunately not have graced his dining table.

Through a lifetime friendship with Sir Horace Mann, Walpole was able to acquire rare treasures from the continent. Their correspondences, spanning from 1740 to Mann’s death in 1786, includes a total of 1,735 letters. The sheer breadth and scale of their exchanges was not unnoticed by Walpole who wrote, ‘A correspondence of near half a century is, I suppose, not to be paralleled in the annals of the Post Office!’

From personal divulgences to purchases of artworks, Walpole and Mann’s letters inevitably discuss porcelain. Given Mann’s situation in Florence, the topic of Doccia porcelain at its inception appears. Writing to Walpole, Mann relates his conversation with the Marquis Carlo Ginori (1702-1757), ‘He talks to me much about cobalt and zingho, two minerals which he says are found in England, and which would be vastly useful to him in composing the colours for the painting his china.’

Upon receiving a pair of Doccia vases from Mann, Walpole opines, ‘The form of the vases is handsome, the porcelain and gilding inferior to ours, and both to those of France; as the paste of ours at Bristol, Worcester and Derby is superior to all but that of Saxony…’

Walpole’s correspondences demonstrate the wide range of his connoisseurship, indicating close study and familiarity within and across mediums. With his ceramics collection, mostly displayed in the China Room, he was able to conduct comparative analysis looking at style and execution. In Walpole’s Description of the Villa of Mr Horace Walpole, he records a number of English ceramics, particularly Chelsea where he possessed ‘Two white salt-cellers with crawfish in relief’. These examples of the earliest Chelsea production reveal Walpole’s patronage of the burgeoning manufactory but as production continued into the Gold Anchor Period, Walpole, upon seeing the Mecklenburg Service commissioned by King George III and Queen Charlotte, remarks, ‘I cannot boast of our taste; the forms are neither new, beautiful, nor various. Yet Sprimont, the manufacturer, is a Frenchman; it seems their taste will not bear transplanting’.

By acquiring multiples, Walpole and his friends were able to compare artistic production across historical periods and cultures to isolate individual styles and movements. For Walpole, his collecting practice was informed by scientific method and guided by a desire to balance the beautiful and the sublime within his neo-Gothic home. His assembled collection displayed in Strawberry Hill brought together far-flung treasures to provide a gathering place for friends and visitors alike to share in Walpole’s dream, which he reflects upon where he writes, ‘Our wishes and views were given us to gild the dream of life, and if a Strawberry Hill can soften the decays of age, it is wise to embrace it, and due gratitude to the Great Giver to be happy with it’.

Following Walpole’s death in 1797, his estate was inherited by his cousin’s daughter, the sculptress Anne Seymour Damer (1748-1828). After successive heirs spent their fortune, the contents of Strawberry Hill was sold off in a public auction in 1842. Strawberry hill, itself, eventually fell into disrepair, requiring vast sums to restore and maintain itself to its former glory.

Fortunately, the Grade One listed building was registered with the English Heritage Trust, where the Strawberry Hill Trust was formed in 2002 to restore the building and to make it accessible to the public. With generous support from the Heritage Lottery Fund, The World Monuments Fund, English Heritage, the local community and a number of Trusts and Foundations, £10 million was raised and the restoration of Strawberry Hill House & Garden was accomplished. It was opened to the public in October 2010!

While the historic house and gardens are temporarily closed, visitors can still experience its famed architecture by visiting:

https://www.strawberryhillhouse.org.uk/

Virtual tours can also be accessed by downloading the free Strawberry Hill App for both iOS and Android phones.